On July 15, 1594, officials in Puebla de los Ángeles arrested fifty-eight-year-old Margarita de Sossa (b. 1536) on charges of witchcraft (brujería) and hauled her from the city where she then resided, Puebla in New Spain, to the secret jails of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in the viceregal capital, México (present day Mexico City). As was typical in inquisitorial trials, Sossa did not know why she had been arrested.Footnote 1 However, she soon informed the prosecutors in her trial that she was innocent; her spiteful enemies in Puebla must have furnished any accusations levied against her. Sossa had harbored such enemies, she explained, because some years earlier she had testified against Bargas Machuca, a resident of Puebla, regarding his crime of incest against a young Indigenous Chichimeca girl to whom both Sossa and Machuca served as godparents. When inquisitors in Mexico City eventually heeded Sossa’s calls to investigate the previous court case in Puebla where witnesses had supposedly provided false testimonies against her, inquisitors discovered a lengthy divorce petition dating from 1588 that Sossa had instigated against her husband, Antonio Álvarez.

Sossa’s biography provides striking insights into how she conceptualized freedom in terms that included – but were not limited to – legal manumission. As a domestic slave in urban Puebla, Sossa had been a slave-for-hire (jornalera), whose owner permitted her to hire out her labor as a healer and to keep a portion of her wages. In time, she raised enough money to buy her own freedom.Footnote 2 But that was only one moment in a lifetime of continued attempts to obtain different degrees of freedom. Her transatlantic biography offers a rare insight into the life of first an enslaved and, later, a free black woman in late sixteenth-century Puebla, who sought to establish various degrees of freedom for herself. Entrepreneurship, self-fashioning, self-transformation, and legal maneuverings were central to Sossa’s attempts to claim freedom: from being owned and refusing that her owner abuse her body, to owning others; from marriage, and eventually the opportunity to purchase her own manumission, to seeking freedom from marriage through divorce; and from serving others, to being a proprietor. Her biography shows that obtaining legal manumission was not always equivalent to living with freedom, particularly if married to an abusive husband, and if successes inspired the envy of neighbors. What follows is a discussion of Sossa’s various paths to seek and define greater degrees of freedom for herself, and the many life-threatening risks that she encountered as a result.

Freedom in Degrees: From Slavery to Manumission

After four or five days languishing in a prison cell in the Inquisition’s secret jails in Mexico City without any clarity as to why inquisitors had arrested her, Sossa was summoned to appear at the first hearing for her trial on August 8, 1594. In that hearing, inquisitors described Margarita de Sossa as a free black woman who was born in Porto in Portugal and who lived in Puebla, where she was married to a shoemaker and where she maintained a trade as an inn-keeper.Footnote 3 The description employed by the prosecutor relied on language that included Sossa as a member of the respective communities where she had been born and resided in the Iberian empire: “Margarita de Sossa, black, native (natural) of the city of Oporto in the kingdom of Portugal, wife of Antonio Álvarez, a Portuguese shoemaker who left to China. A resident (vecina) of the city of Puebla de Los Ángeles where she has as her trade to lodge guests (hospedar a huespedes), of approximately fifty-eight years of age.”Footnote 4 This succinct biography of Sossa betrayed no hint of the long history of violent enslavements and multiple forced displacements across the Atlantic world that she had endured in her lifetime as an enslaved woman, nor of her multifaceted attempts to obtain various degrees of freedom. In contrast, in a separate testimony a few months earlier in Puebla, a free black man and vecino of Puebla named Francisco Gallardo noted Sossa’s former history of slavery by describing the visible branding on Sossa’s face that a former slave owner burned on her skin in order to mark her status as a slave: “Margarita de Sossa, Portuguese and mulata, who is not entirely black (no es bien negra), and with some letters on her face (rostro), who is free, and married with Antonio Álvarez, Portuguese and a shoe-maker who is at present in China, and she gives beds and food in this city.”Footnote 5 Both the inquisitors in México and Gallardo clearly noted that Sossa was free and that her trade involved providing beds and food. Found among her belongings when inquisitors arrested Sossa in Puebla were five mattresses and a new wooden bed, suggesting that she could provide accommodation to at least half a dozen customers per night.Footnote 6

During Sossa’s first hearing for her inquisitorial trial in México on August 8, 1594, she informed her interlocutors that she had endured a grueling life of violent captivity and sexual abuse across the Atlantic at the hands of various slave owners. In the genealogical biography that Sossa provided to inquisitors, she explained that her father was a merchant named Juan de Cáceres from Oporto and that her mother was “Lucia negra” from the Island of Madeira.Footnote 7 Sossa did not explain whether her mother had been enslaved during Sossa’s lifetime, nor whether her mother had been enslaved to Sossa’s father. Instead, Sossa’s discurso de vida – a biographical narrative that inquisitors asked defendants to recount during their first hearing – described how she grew up enslaved in the house of her female owner, Señora Lucrecia de Cisna. Sossa recalled that her owner took Sossa to Lisbon when she was twenty years old and sold her to a Flemish man. Sossa’s new owner reportedly forced her to become his amancebada, a term used in the period to describe unmarried cohabiting lovers. In other words, Sossa endured a grueling time of being subjected to regular acts of rape while enslaved in Lisbon. However – as Sossa testified to the inquisitors – within two or three years, she had informed her owner that she refused to continue living as his amancebada. Sossa did not explain to her interlocutors what measure of resistance she enacted in order to deny her owner access to her body, nor did she dwell on whether she endured physical violence as a result of her refusal to comply with his sexual demands. However, Sossa’s refusal to continue engaging in a carnal relationship with her owner was the first of many acts of resistance that she enacted in her lifetime in order to claim a measure of freedom.

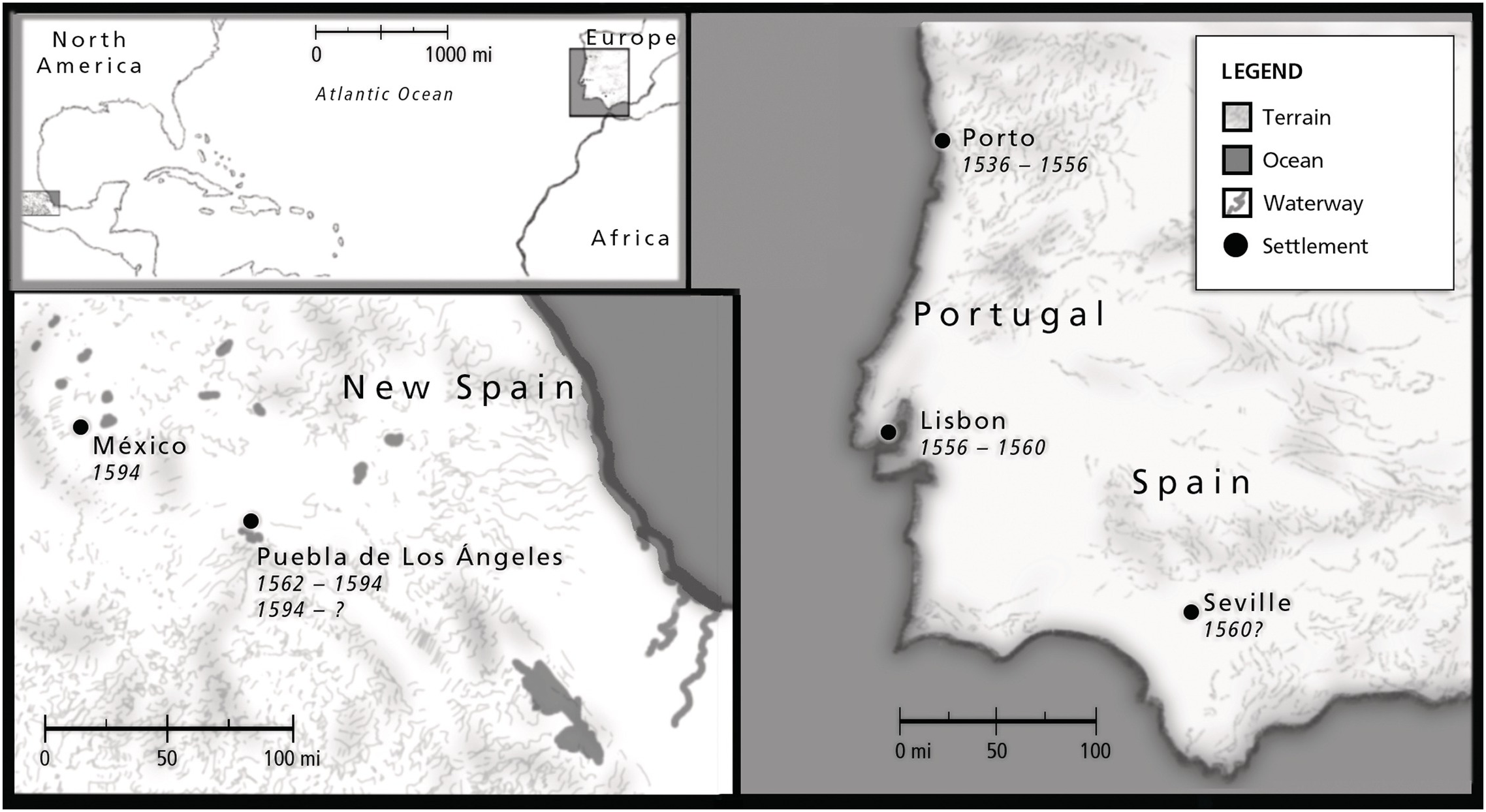

After her refusal, Sossa recalled that her owner sent her from Lisbon to Seville, presumably to be sold in a slave market in that city.Footnote 8 There, a second Flemish slave owner bought Sossa and sent her across the Atlantic to New Spain in approximately 1570. Once Sossa arrived in New Spain, a priest or canon clergy (canónigo) and familiar of the Inquisition reportedly purchased her in the city of Puebla. She was subsequently sold two additional times in that city. Sossa gave no explanation for the multiple sales of her labor and body as a slave, or of her experience of the forced and potentially fatal journey as a slave across the Atlantic Ocean. Nor did she dwell any further on the treatment that she received from her subsequent owners across the Iberian Atlantic. To recap: over the first three decades of her life, seven slave owners bought and sold Sossa across four cities of the Iberian Atlantic – Oporto and Lisbon in Portugal, Seville in Castile, and Puebla de los Ángeles in New Spain (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Margarita de Sossa’s journey

This map shows the rough distances that Sossa might have traveled in the Iberian Atlantic.

By the mid-1580s, Sossa’s odyssey of enslavement to numerous owners had landed her in Puebla, a city in the central highlands of Mexico that had been founded by Castilian colonists in 1532 and served as a major commercial and communication crossroads between the Atlantic port town of Veracruz, the inland town of Jalapa, and Mexico City.Footnote 9 By the mid-sixteenth century, Puebla figured as an important city on the royal road (camino real) between Veracruz and México, with a constant influx of temporary dwellers, as travellers, merchants, soldiers, members of religious orders, and colonial officials passed through the city en route to other sites in New Spain, the Caribbean, the Pacific, and the Iberian Peninsula. By the 1540s and 1550s, a significant slave market had developed in Puebla, where merchants sold African slaves from Upper Guinea and Indigenous war captives from the Mixtón War in New Spain.Footnote 10

Enslaved individuals in Puebla’s private households had some degree of autonomy in the city, or at least more so than those destined to laboring in mines and textile production. For example, enslaved women washed clothes in Puebla’s public streets, and were a notable presence in the city market.Footnote 11 Puebla also had a significant demographic of free black vecinos; there were a few black vecinos registered in the town council records in the mid-sixteenth century, and, by the 1570s, contemporaries estimated a black population of some 500 black men and women (most of them enslaved) as well as many people of mixed African descent (mulatos).Footnote 12 Free African-descended men and women who rented or owned land or inns in rural regions between Jalapa and Puebla in the late sixteenth century also maintained commercial ties in Puebla, sometimes opting to sign notarial contracts in Puebla as well as in Jalapa, and came into contact with the black residents of Puebla when conducting business in the city.Footnote 13

The details of Sossa’s first years of living enslaved in Puebla were etched in the historical archive because her first owner in Puebla, canónigo Alonso Hernández de Santiago, wrote a letter to inquisitors in Mexico City in 1594 to provide context for Sossa’s case. He explained,

this Margarita de Sossa was my slave and I bought her after she came from Spain, and I was the first owner [amo] that she had in this land and after that she had two others, one was Alonso de Ribas, textile-mill owner (obrajero), whom I sold her to, and Ribas sold her again to another owner, and in whose power Antonio Álvarez liberated her, having married her before. The reason why I sold her was because she spoke too much and used bad language (por no tener buena lengua), even though she was a good servant.Footnote 14

During the years that Sossa first lived in Puebla, she may have obtained a slightly greater degree of freedom than in Iberia, even though she remained enslaved. Sossa testified, both in her litigation suit in Puebla in 1588 and in her inquisitorial trial of 1594, that she had maintained a labor-for-hire arrangement (jornalera) with her owner in Puebla.Footnote 15 In practice, Sossa likely worked as a healer, tending to the maladies of various residents of the city who sought her services, while her owner kept a percentage of her wages. It is possible that Sossa might have lived independently from the three men who owned her during her early years in Puebla. Certainly, in the nearby town of Jalapa it was not uncommon for slave owners to send their slaves to live in the Veracruz port where they would rent out their labor, while slaveholders would reside in Jalapa and receive a portion of their slaves’ wages.Footnote 16 While enslaved in Puebla, Sossa was also permitted to marry a free Portuguese shoemaker named Antonio Álvarez.

By the mid-1580s, Sossa had obtained her freedom, at least in legal terms, after an excruciating lifetime of multiple sales and forced displacements across the Atlantic world. Either Álvarez or Sossa – or both husband and wife – negotiated to purchase Sossa’s freedom from her owner. After obtaining a pronouncement of her legal manumission, Sossa became known as a free resident (vecina) of Puebla and testified that she developed a profitable trade as an innkeeper. Sossa did not mention whether she also continued to labor as a healer upon manumission, or whether the healing activities were linked to her role as an innkeeper or provider of beds and food. Once she purchased her own freedom, Sossa also opted to publicly distinguish her free status and wealth to the community in Puebla by becoming a slave owner: she purchased a black female slave for her personal service.Footnote 17 Perhaps, through slave ownership, Sossa hoped to assuage any doubts that Poblanos may have harbored about her status as a free woman, doubts that may have been heightened due to the visual branding on her body that told a story of a history of enslavement. There was nothing more valuable or desirable in late sixteenth-century Puebla than owning a black slave.Footnote 18

Freedom after Manumission: A Petition for Divorce

After obtaining manumission following a lifetime of violent captivity across the Atlantic world, Sossa found that her freedom remained curtailed. She found herself trapped in a violent marriage with a husband who physically restricted her movements, threatened her life, and failed to fulfill his marital financial, sexual, and cohabiting duties and obligations. In an attempt to gain a greater degree of freedom, in 1588, Sossa took the unusual measure of petitioning that the highest legal official (alcalde) of Puebla grant her a divorce from her husband.Footnote 19 Sossa did not request an annulment to the marriage, but rather an ecclesiastical divorce, which was “a permanent or temporary legal separation that suspended the obligation of marital cohabitation without dissolving the marriage bond.”Footnote 20 A pronouncement of ecclesiastical divorce did not signify the freedom to remarry, but instead permitted the parties the “right to live separately, to settle their estates, and to manage their affairs independently,” while retaining “all the other incidents of marriage, including the responsibility of the husband to economically support his wife and the requirement of sexual chastity.”Footnote 21 Ecclesiastical divorce was not common in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century New Spain and was “an absolute last resort” for couples who “had extremely troubled and often violent relationships.”Footnote 22

Sossa’s litigation for divorce and the legal strategies that she and her lawyer employed shed light on the importance of conceptualizing of freedom in degrees, and of interrogating the significance – in terms of lived experience – of a legal pronouncement of freedom. Typical petitions from wives who asked for ecclesiastical divorces cited their husbands’ excessive and irrational violence, lack of financial sustenance, and scandalous adultery.Footnote 23 Sossa drew on these common themes in her 1588 petition for divorce by describing her husband’s multiple failings: he had failed to provide for her as she sustained the pair through her own labor; he had failed to live a married life with her as he ate and slept alone, and was engaged in a sexual affair with a married woman, which was a matter of public notoriety and scandal across the entire city of Puebla; and he exerted excessive violence against her, which endangered her life.Footnote 24

The most egregious of Álvarez’s actions, according to Sossa, was his theft of an enslaved black woman whom Sossa owned. According to Sossa, Álvarez had stolen her property in order to furnish his lover with a gift, while a servant (criada) of her husband’s lover was now acting as Álvarez’s personal servant. In other words, Álvarez had stolen one of the public symbols of Sossa’s status as a free property-owning woman. Not only had Sossa lost her own slave as a result of her husband’s theft, but her husband had also benefited from the service of another servant. All of this, noted Sossa, was “public and a thing of great scandal.”Footnote 25 Her husband had tried to silence Sossa on the matter, but she noted, this is all “public and notorious in all of the neighborhoods (vecindades) where I have lived.”Footnote 26 Sossa’s description of the flagrant theft and subsequent regifting of her slave property is indicative of Sossa’s attempts to mark her status as a free woman through the public symbolism of slave ownership.

Sossa pleaded for a divorce because she foresaw no other remedy for ending the terrible life and dangerous insecurity that she endured under Álvarez’s wrath. Her husband physically harmed her on a regular basis.Footnote 27 Sossa described a series of violent incidents that left her on the verge of death. She was subjected to

beating, whipping, caning, and thrashing [that] cruelly left my body injured and mistreated and one time he took out a dagger towards me … and further, he gave me a very grave injury on my forehead of which I had a risk of death. Another time, he broke three ribs of my body and another time he broke me … and those times I was on the verge of death.Footnote 28

Sossa described the impossibility of enduring a married life with Álvarez because he physically harmed her so regularly and often locked her in a room with a key in order to prevent her from complaining to the city’s alcalde or seeking a healer to tend to her injuries.Footnote 29 Further, Álvarez had also threatened to either kill Sossa or send her to Portugal.Footnote 30 Sossa pleaded that the alcalde of Puebla grant her a divorce and allow her to live alone and apart from her husband, specifying the need for the two to sleep in different rooms.Footnote 31 She also requested that the Puebla court prevent Álvarez from communicating with her and prohibit him from physically abusing her any further.

In the divorce petition, Sossa also made important assertions about her husband’s inadequacy in fulfilling his financial obligations to his wife. She explained that her husband had failed to provide sustenance for her. She contrasted her husband’s failures or unwillingness to support her financially with the record of her own independent economic productivity, both while enslaved and after she obtained manumission. Sossa asked that the court order her husband to continue to provide for her because she had earned everything in Álvarez’s possession, noting “and there is no more to consider … beyond that I am a woman who has earned everything that he has and he is obligated to give it to me.”Footnote 32 Sossa told the court that Álvarez had hidden his property – that included 4,000 pesos that Sossa had earned through her own “sweat and labor” – with the intention of killing her and escaping with the fruits of her earnings.Footnote 33 Sossa also noted that she had provided all of the resources for their marriage and purchased her own manumission. Sossa explained that she had given Álvarez the money to purchase her freedom through her own income generated from her labor as a healer, noting “the money with which I liberated myself was from my work and sweat and not that of my husband.”Footnote 34 Sossa thus positioned her manumission as an act of self-purchase resulting from her labor-for-hire arrangement with her former owner. Her husband, Sossa thus argued, played no part in her pursuit of legal manumission.

A Community Affair

The Sossa-Álvarez divorce proceedings became a moment of public reckoning about how to define a legitimate marriage, a husband’s responsibilities within such a sacrament, and a wife’s freedom and rights within a marriage. A diverse cross-section of Poblano society played a role in assessing the legitimacy of the Sossa-Álvarez marriage. Sossa called on twenty-four witnesses to attest to the many injustices and dangers of her marriage.Footnote 35 Those who testified for her included merchants, slave owners, two black slaves, female widows who resided in Puebla, one of Sossa’s former owners named Alonso de Ribas, and a young girl who labored as Sossa’s and Álvarez’s servant, named Inés Pérez. Álvarez also sourced a varied cast of characters to act as witnesses for his defense.

The testimonies for Sossa provide a striking insight into social relations in Puebla. Witnesses described visiting or dining in the private space of Sossa’s and Álvarez’s home, sighting Sossa’s injuries while in Puebla’s public spaces, and discussing the magnitude of Álvarez’s violence with Sossa. Sossa’s witnesses confirmed that Álvarez beat Sossa, and reported seeing the grave wounds to her body on various occasions; others confirmed that Álvarez would often eat and sleep alone without Sossa. Some of the witnesses, including her former owner, Alonso de Ribas, also recalled that Sossa’s husband was poor when the couple married, and described Sossa as a hard worker who had earned all of the capital in the couple’s possession and who had manumitted herself through money that she had earned as a healer.Footnote 36 Eventually, Sossa’s first owner in Puebla, canónigo Santiago, also testified for Sossa in the divorce proceedings against her husband.

Successful divorce petitions were rare in New Spain.Footnote 37 Only 13 percent of the known 110 ecclesiastical divorce petitions between 1548 and 1699 resulted in a pronouncement of divorce.Footnote 38 Due to the low success rate for divorce petitions, historians have theorized that wives’ litigated for ecclesiastical divorces not with the hope of obtaining a pronouncement of divorce, but because they knew that if judges granted that their cases be heard, wives would be placed in a protective custody or deposit (depósito), usually in “a private house or institution and out of the control of her husband for the duration of the legal process.”Footnote 39 Seventy-five percent of ecclesiastical divorce petitions remained unresolved, a figure that suggests that wives might have hoped to remain in protective custody in a depósito for lengthy periods of time, if not permanently.Footnote 40 Sossa, thus, perhaps did not hope for a pronouncement of divorce, but rather for the freedom to live separately from her husband and to receive maintenance from him while she resided in a temporary or permanent depósito. Let us recall Sossa’s initial petition that the court: (1) allow Sossa to live alone and distanced from her husband, specifying the need for the two to sleep in different rooms; (2) prevent Álvarez from communicating with her and prohibit him from physically abusing her any further; and (3) order her husband to continue sustaining her with food.Footnote 41 If Sossa’s aim was to be placed in a depósito or shelter (depositada), she emerged somewhat victorious from the legal proceedings as the Puebla court ordered that her husband sustain her with an advance payment every year of 150 pesos de oro comun while the case was ongoing and she remain sheltered in another house.Footnote 42 Given the high rate of unresolved and pending divorce cases in New Spain in the period under study, Sossa might have judged that her success lay in compelling the judge to allow for the divorce case to proceed and placing her in a depósito and ordering that Álvarez sustain her, rather than any actual resolution of the case per se.

Perhaps Sossa viewed her placement in a depósito away from her husband and his court-ordered contribution to her sustenance as a means to achieve liberty. Her incensed husband certainly suggested that Sossa’s depósito was a ploy for her to gain greater freedom. Launching an appeal against the order that he pay sustenance, Álvarez complained that Sossa was roaming the streets of Puebla at night as though she were not a married woman and conducting business independently. He explained that she had

maliciously sought a divorce in order for her to have the freedom to walk in her business (anduras) and vices because there is no one who can detain her for more than an hour in the house, and she has not adhered to the depósito in which your majesty put her, because every day she is not in the house for more than an hour and she is instead walking the streets from the morning until the night and is accompanied by Juana Limpias, a free black woman.Footnote 43

In short, Álvarez accused Sossa of litigating for a divorce in order to enjoy the freedoms of an unmarried woman while residing in the depósito. Álvarez was particularly preoccupied that his wife was enjoying the freedom to walk wherever she wanted and at whatever time she desired.

It is unclear whether the case reached a final resolution, although the undated summary note that arrived to the Holy Office of the Inquisition in México in 1594 implied that a judgment had decreed that the couple resume cohabitation and married life. However, in 1592, within three years of Sossa litigating for divorce, Álvarez had abandoned the city of Puebla and the viceroyalty of New Spain for the Philippines – perhaps due to the economic burden of high maintenance responsibilities – never to return.Footnote 44 Seemingly the pair did not maintain contact thereafter. On the one hand, Álvarez’s departure and Sossa’s depositions in the subsequent inquisitorial trial implied that the couple became completely estranged, suggesting that Sossa escaped his violent wrath. Further, in the years since his departure, she testified to working a profitable trade as an innkeeper in Puebla.Footnote 45 Her former owner, canónigo Alonso Hernández de Santiago, explained in a letter to inquisitors in México in 1594 that Sossa’s “trade and way of living has been and is to provide food and beds in her house to some people and she lives in the small houses and this trade she has used in the absence of her husband.”Footnote 46 Perhaps Sossa’s trade also explains how she was able to secure a loan from a vecino of the city of México to pay her bail during her Inquisition trial, allowing her to await the verdict while living freely in the viceregal capital rather than languishing in the secret jails of the Inquisition.Footnote 47 Sossa’s ability to command a loan for her bail implied that she possessed some social capital within personal or trading networks that spanned Puebla to México, and that she found means to send word to one or more of her contacts in México after her arrest. On the other hand, Sossa continued to be married to Álvarez and would endure public notoriety for her attempt to divorce. The supposedly false testimonies provided about Sossa’s witchcraft to the Inquisition by her Puebla enemies demonstrate just how dangerous such public notoriety could become.

A Case within a Case

Sossa’s 1588 petition for divorce became the center of her defense strategy six years later in her 1594 inquisitorial trial. Sossa responded to the accusations levied against her by suggesting that some people in Puebla – those who were her capital enemies and harbored much hatred against her – must have provided false evidence about her life.Footnote 48 She explained that such enemies had falsely testified about her being a witch (bruja) six years earlier and that they had already been imprisoned in Puebla for the crime of providing false testimonies. In inquisitorial proceedings, testimony or accusations based on personal acrimony were dismissed. Sossa knew as much, and accordingly developed the strategy during her trial of claiming that her enemies must have furnished accusations against her. In the four inquisitorial hearings for her case between August 8 and 22, 1594, Sossa refused to discharge her conscience about any crimes that she may have committed. Instead, in each hearing, Sossa reaffirmed that people who hated her in Puebla, and who “had threatened her and promised to do all the bad that they could to her” must have provided false testimonies.Footnote 49 Sossa demanded that inquisitors seek the transcript from a legal proceeding from six years earlier in Puebla, in which a number of witnesses had falsely accused her of witchcraft and had been imprisoned for their offences, including a free black man named Francisco Gallardo.

The commissary (comisario) of the Inquisition for Puebla and the Archbishopric of Tlaxcala who was responsible for collecting information about any potential crimes in the region was canónigo Alonso Hernández de Santiago, who had been Margarita de Sossa’s first owner in Puebla. Santiago had written to inquisitors in México in 1594 to describe the history of the false testimonies against Sossa in Puebla. In that letter, Santiago explained that witnesses in Puebla had testified to him in February 1594 about Sossa’s reported brujeria, but he noted that

in a court case that she had with the ecclesiastical court (audiencia obispal) against her husband to petition for a divorce, some people testified that Sossa had put some powders in the food, and that as I had noticed it, and that I punished her for it. It was a false testimony, and that is what I declared in the court case.

Santiago assured inquisitors that he had sold Sossa because she talked too much and not because she was a bad servant, nor because she was a bruja as some people in Puebla had claimed.Footnote 50 Perhaps the arrival of Santiago’s letter convinced inquisitors to duly acknowledge the potential danger of relying on accusations furnished by witnesses whose statements might have resulted from hatred or personal acrimony, because they instigated the lengthy measure of requesting the divorce case from Puebla that Sossa had cited. In the meantime, inquisitors permitted Sossa to live freely in the viceregal capital on bond while her trial remained pending, noting that a vecino of México was willing to pay a bond for her freedom.Footnote 51

Upon receiving from Puebla the transcripts of the 1588 divorce case, the inquisitor decreed that a free black man named Francisco Gallardo had provided false testimonies to portray Sossa as a bruja as a result of his hatred towards her because of her litigation for divorce against her husband in 1588.Footnote 52 On September 26, 1594, two months after her initial arrest, inquisitors granted Sossa license to return to Puebla until any new information arose pointing to her culpability. To fulfill the bureaucratic need for evidence (even in those cases that proved inconclusive), inquisitors included the entire transcript of Sossa’s litigation for divorce in the file of Sossa’s inquisitorial trial. As a result of this bureaucratic precaution, her divorce case in Puebla has been preserved over the centuries as though it were the transcript of her inquisitorial trial in México.

Conclusion

Freedom for Sossa was a plural, varied, and fractional legal status and lived experience that emerged after years of negotiations for miniscule degrees of freedom across different contexts in the Iberian empire. Sossa put an end to being raped by one of her earlier slave owners in Lisbon and did so regardless of the possible violent or fatal consequences that such a refusal might entail. Some years later, when enslaved to a different owner in Puebla, she negotiated for the right to marry, and possibly also to labor as a jornalera, and therefore the freedom to rent her labor in Puebla, while keeping a small percentage of her earnings. While enslaved, Sossa also negotiated for the opportunity to purchase her liberty. Upon gaining a legal pronouncement of liberty and living as a vecina, Sossa felt trapped in a marriage with a husband who failed to provide for her, subjected her to scandal and public ridicule through extra-marital affairs and the theft of her slave property, and harmed her through extreme physical violence. In those early days of her legal manumission, Sossa was thus free by law, but trapped in a violent marriage that denied her any sense of liberty at all. Once again, Sossa sought to negotiate her freedom in degrees, and she took the unusual step of petitioning for an ecclesiastical divorce for which she collected a host of witness testimonies to support her litigation. During that litigation, she became the subject of accusations of witchcraft, and sought the testimony of her former owner, canónigo Santiago, to prove her innocence. After the courts ordered that her husband continue to maintain her with a specific amount every year, perhaps Sossa finally experienced some respite because her husband then abandoned New Spain for the Philippines.

Still, Sossa’s arrest by the Inquisition in Mexico City demonstrates how her freedom was contingent, and highlights how malicious and notorious gossip could easily result in the loss of a hard-earned liberty through an inquisitorial trial. Punishments – if found guilty of accusations of witchcraft – could be severe, if not fatal, stretching from a permanent or temporary exile (destierro) from the city or viceroyalty where she resided, to having to endure public lashings and other forms of public humiliation in the cities of México or Puebla, to – albeit more rarely – a death sentence in a public act of the faith (auto-da-fé). Sossa’s knowledge of inquisitorial procedure allowed her to convince inquisitors that they should investigate her divorce proceedings from six years prior in the city of Puebla. The strategy paid off and led to her acquittal and a license to freely return to Puebla until any further evidence of her culpability might come to light.

Thereafter, Sossa disappeared from the archival record; we do not know whether she was re-arrested by the Inquisition at a later date, or whether she remained in Puebla, or whether her estranged husband ever returned to New Spain. Sossa thus endured an epic and grueling journey towards freedom that she continuously negotiated in degrees throughout her life. Whether seeking relief through legal strategies, entrepreneurship, or personal interactions and relationships, she continued to seek and obtain greater degrees of autonomy. Even as she did so, the meanings and ways that she conceptualized her freedom continued to change.